16 May WAITING

The cape winelands are a hilly region east of Cape Town in South Africa. The views of the mountains are spectacular, the sunrises send streaks of pink and purple across the skies as the clouds roll over the tops of the peaks into the valley.

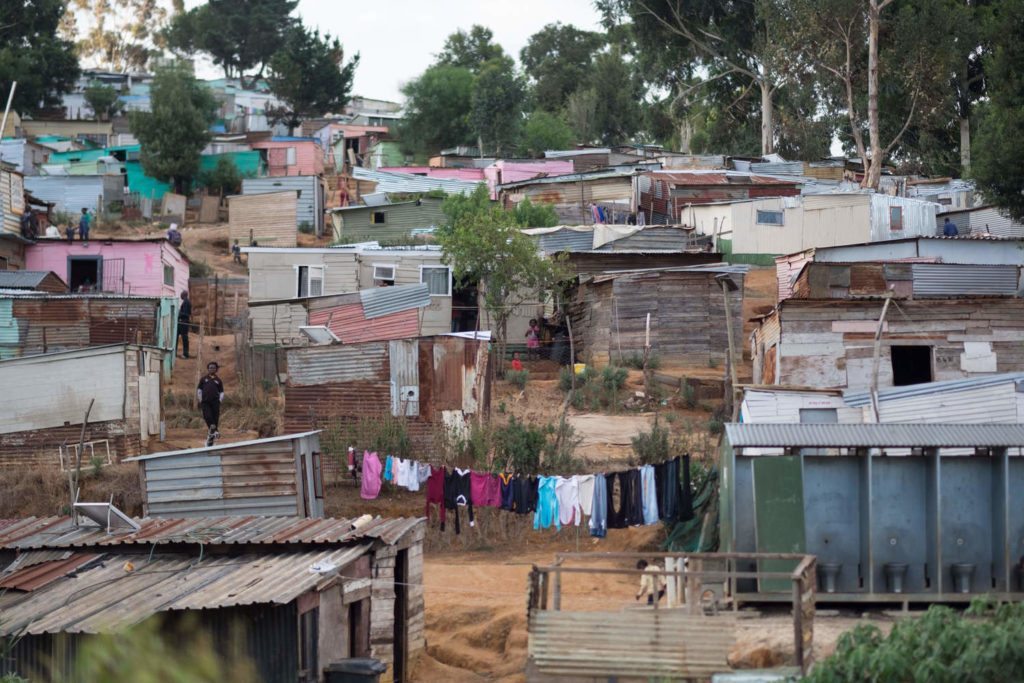

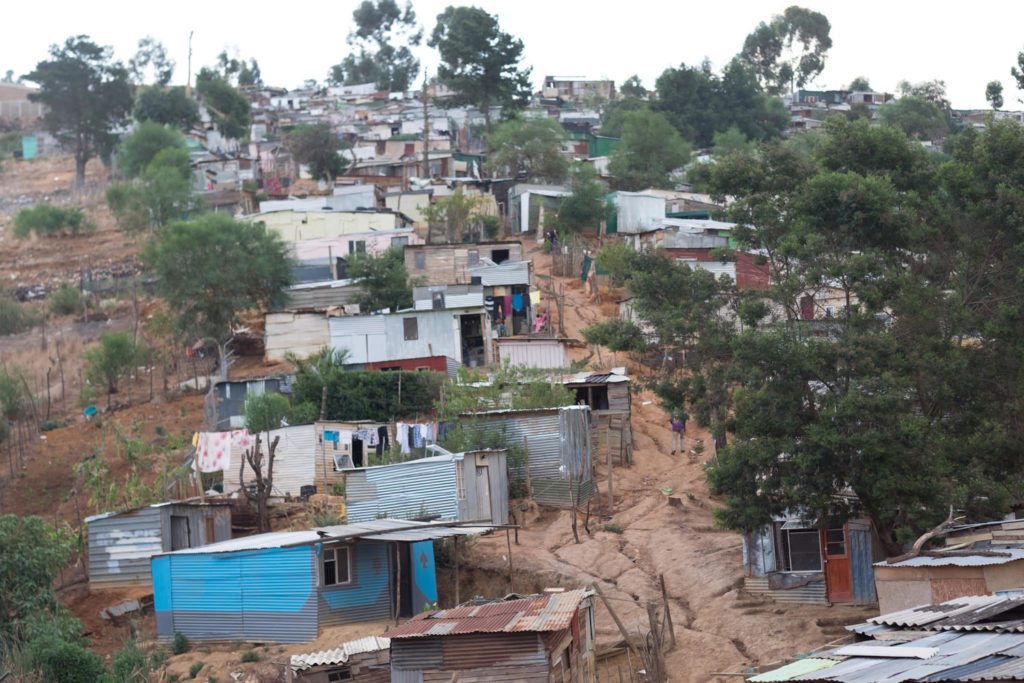

Standing on one such hill outside of the town Stellenbosch, the wind whips around rattling the roofs of the tightly packed shacks here in Enkanini. Since most of the land in Stellenbosch is occupied by upper and middle class housing, even the neighboring township, Kayamandi, could not absorb all the people needing housing in this area, so Enkanini grew out from there. Enkanini is an informal settlement (which means it is technically illegal) and it is estimated that about 10,000 people live here, mostly in shacks made from corrugated tin. These informal settlements are a relic of apartheid and forced segregation.

For a country working to overcome its adverse past, the South African constitution (the current constitution was drafted by those elected in 1994 in the first non-racial elections) placed responsibility on the government to ensure that basic services would be expanded to all citizens, within the limits of available resources. These basic services included electricity, water, housing, as well as waste removal and sanitation.

In Enkanini, there are a few shared restrooms and water pumps for the community to access, but very little else in terms of infrastructure.

So what does it actually mean that South Africa has deemed electricity a basic need and therefore a constitutional right? Damian Conway from Stellenbosch University shed some light on the complexities of this “constitutional right†and the realities on the ground.

“In South Africa there is a constitutional right to “free basic services” only IF a citizen is deemed “Indigent”. To be eligible for indigent status the household that the citizen lives in needs to collectively earn below a certain threshold (about R3500/month). The process of being registered as indigent is normally rather onerous, requiring individual applications with significant submissions like earnings records, marital status, declarations for children, etc.

Nevertheless, should you qualify, and should you live in an area where services are available, then you are entitled to your free monthly allotment from the local municipality. In the case of electricity it is normally 50kWh of free electricity/month. However you need an account with the municipality, you need to be connected to the grid and you need to buy electricity before you get any free electricity.

In sub-Saharan Africa, 62% of the urban population lives in slums (according to the UN Habitat State of the World’s Cities 2012/2013 report), and this number is growing. So how would these people obtain their basic right to electricity if they are not connected to the formal grid?

The simple answer to this is, you wait.

“If you live in an area where there are no services, then you cannot get your free entitlement, and there is very little recourse for you other than to wait. But the wait for services to arrive can often be decades.†– Damian Conway

Waiting. Waiting to be recognized. Waiting for help. In this period of waiting, devastating fires have destroyed homes and taken lives due to use of open flames and unstable illegal connections to electricity. Students from Stellenbosch University saw what was happening, spoke with residents in Enkanini, and the Sustainability Institute decided to do something about it.

This is when the iShack project was born. [Watch “Daniel” below]

Brief bio on the iShack Project: The iShack Project is large-scale utility that provides off-grid solar electricity, on a subsidised, pay-for-use basis, to residents of an informal settlement in Stellenbosch, South Africa. This is a grant-funded, not-for-profit demonstration project. Our mission is to develop a nationally relevant and replicable model for upgrading urban informal settlements in an incremental and financially sustainable way, using modular renewable energy. We have to-date provided the service to over 1000 households and, funds-permitting, will continue expanding the service to the entire community (over 2500 households), as well as launch replication projects elsewhere in South Africa. At the heart of the model is the idea that members of the community participate in the delivery of the energy service. Selected residents are recruited as “iShack Agents”, and trained to install and maintain the solar systems and to market the service within their community. Different energy and pricing packages are offered to end-users. The basic electricity service powers lights and low energy media (cell-phones, radios, etc). Upgrades include television, music-systems, dvd players, and even fridges. The income from end-user fess together with a small operating subsidy (per end-user), provided by the local municipality, ensures that the service can be operationally self-sufficient once the utility has reached a certain scale.

Read more about this amazing project and see how you can get help and get involved.